Bildestørrelse og oppløsning er to begreper som fort kan skape forvirring i forbindelse med digitale bilder. Årsaken er at de hver for seg kan vise til helt forskjellige ting, og i noen tilfeller også handle om det samme.

Bildestørrelse brukes som betegnelse på:

- Antallet bildepunkter i et bilde

- Størrelse på bildet ved utskrift

- Hvor mye lagringsplass bildet tar på minnekortet eller datamaskinen.

Oppløsning brukes om:

- Antallet bildepunkter i et bilde

- Hvor mange bildepunkter man har per cm eller tomme ved utskrift

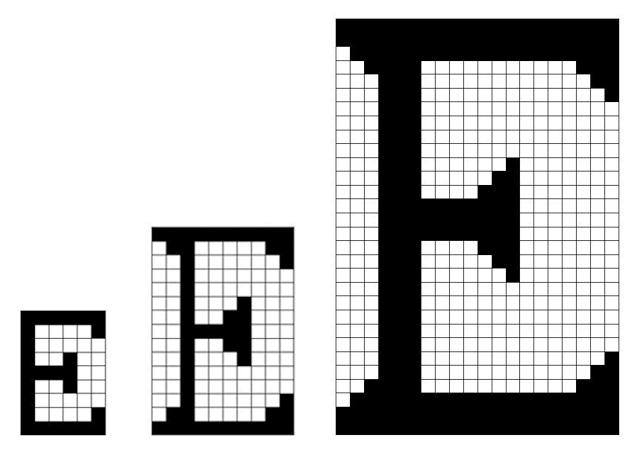

Med et kamera med en sensor på 20 MP (megapiksler) kan du ta bilder med rundt regnet 20 millioner bildepunkter. Jo flere bildepunkter du har, jo større må da bildet selvsagt bli. Samtidig er det slik at jo flere bildepunkter et bilde har, jo flere detaljer kan det gjengi. Jo flere detaljer et bilde kan gjengi, jo bedre oppløsning har bildet. Figur 1 viser begge forhold: Flere bildepunkter gir både større bilde og bedre oppløsning.

Ved utskrift handler naturlig nok bildestørrelse om hvor stort bildet blir i cm eller tommer (2,54 cm per tomme). Også her handler oppløsning om hvor mange detaljer som gjengis, men nå forstått som en kvalitet bestemt av hvor mange bildepunkter utskriften har per cm eller tomme. Jo flere bildepunkter per cm/tomme, jo bedre oppløsning. Dersom man forsøker å skrive ut et bilde i en størrelse som er for stor i forhold til antall bildepunkter i bildet, vil man kunne se bildepunktene som større eller mindre ruter. Dette skjer fordi de relativt få bildepunktene som bildet har, må forstørres for at de skal fylle tilstrekkelig med plass for at bildet skal bli stort nok.

Med andre ord, jo større et bilde er i antall bildepunkter, jo større format kan det skrives ut i med god gjengivelse av detaljer. La oss tenke oss at hver rute som bildene i figur 1 er satt sammen av representerer 100 bildepunkter. Da vil det minste bildet være 6 x 100 bildepunkter = 600 bildepunkter bredt. Beste trykkekvalitet i ukeblad/magasin krever rundt 300 bildepunkter per tomme. Med andre ord ville det minste bildet bli 600 bildepunkter : 300 bildepunkter/tomme = 2 tommer bredt (5,08 cm). Det største bildet ville være 20 x 100 bildepunkter = 2000 bildepunkter i bredden, med en trykkestørrelse på 2000 bildepunkter : 300 bildepunkter/tomme = 6,7 tommer (16,9 cm). Det er altså antallet bildepunkter som i stor grad avgjør kvaliteten på trykk i forhold til trykkestørrelsen, i alle fall i utgangspunktet. Kvaliteten på bildepunktene og på papiret spiller også inn.

Merk at bildepunktene må stå mye tettere i en utskrift enn på skjerm, for å si det slik. Med en skjermoppløsning på 1920 bildepunkter i bredden, vil et bilde med samme antall bildepunkter, fylle hele skjermen (i prinsippet uansett skjermstørrelse), mens bildet trykket i beste kvalitet vil bli litt mindre enn bildet på 2000 bildepunkter i eksemplet ovenfor (nærmere bestemt 16,25 cm). Det er med andre ord ikke uten videre mulig å få gode utskrifter av bilder man henter på nettet. Til det er oppløsningen på nettbildene som regel for lav.

Til sist, eller kanskje helt først, er bildekvaliteten avhengig av hvor mye plass bildet får lov til å oppta på minnekortet/datamaskinen. Aller best kvalitet får man om man tar bilder i RAW-format. Da lagres all informasjon fra kameraets sensor i bildefilen. Mitt kamera Canon EOS 5D mkIII, tar RAW-filer på 23-30 megabyte. Velger jeg å ta bilder direkte i JPG-format, foretar kameraet en redigering og komprimering av opptaket i henhold til den bildestilen som kameraet er innstilt på, og så kastes resten av informasjonen fra sensoren. Et JPG-bilde med størrelse L (22 MP) vil oppta 4-9 megabyte plass. Bilder i størrelse M og S vil da selvsagt ta enda mindre plass, og samtidig gi bilder med dårligere oppløsning.

Så et svært viktig sluttpoeng: Bildekvalitet i form av oppløsning/detaljrikdom er ikke nødvendigvis sikret om du benytter innstillingen med størst antall bildepunkter (L). På kameraet kan nemlig også stilles inn såkalt «bildekvalitet». Dette handler om hvor mye bildet skal bli komprimert for å oppta mindre plass på minnekortet/datamaskinen, og med dette også hvor mange detaljer som gjengis.

På bildet som viser valg for bildekvalitet på Canon-kamera, står altså bokstavene L, M og S for bildestørrelse ut fra antall bildepunkter i bildet. Vi finner to valg per størrelse, ett for fin kvalitet, og ett for ikke fullt så fin kvalitet (mer komprimert bilde som tar mindre plass på minnekortet). På en del andre kamera, f.eks. Nikon, velges størrelse for seg, og kvalitet relatert til komprimering for seg.