A photographer is a person who writes or draws with light. Hence photography is very much about controlling light. Photographs are made as a light sensitive material within the camera (the sensor) is exposed to light, and a good photographer knows how to let the right amount of light onto the sensor.

So exposure is all about controlling light, and understanding exposure is all about knowing how to make the available light into the right amount of light for the photograph you want to bag.

The Exposure Triangle

I assume you’ve studied the exposure triangle, still I don’t take this for granted in this article so don’t worry if you haven’t. The exposure triangle is a model for introducing and explaining tools for controlling the amount of light, among other things. These tools are:

The aperture: An adjustable opening, usually in the lens, for regulating the flow of available light entering the camera. The shutter: A physical mechanism or an electronic function that controls for how long the flow of light entering the camera is recorded by the sensor. The time span is usually referred to as «shutter speed» or «exposure time». The ISO-setting: An electronic function within the camera calculating the sensor’s «sensitivity» to light, an analogy to photographic film’s physical sensitivity to light.

The Four Section Exposure Circle

But there are actually more tools for controlling the flow of available light into the camera! These are the tools for controlling, influencing or even creating the available light itself:

- Flashguns

- Light panels

- Lamps

- Reflectors

- Filters

- Screens etc.

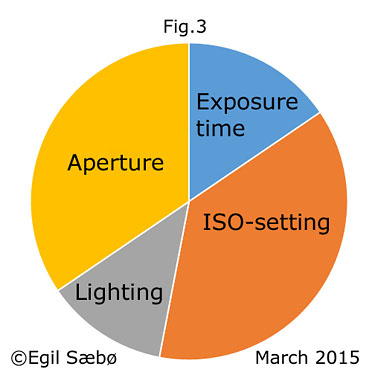

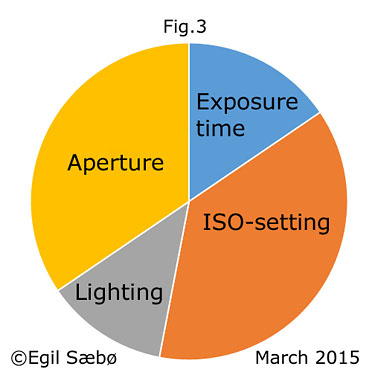

We are not going to explore this latter group of tools as such, but I find this group crucial to mention as I now introduce the four section exposure circle model (FOURSEC) where these tools belong to the section of lighting (representing the available light). The advantage of the FOURSEC model is that it links exposure to the very lighting situation, both directly and visually, a feature lacking in the exposure triangle model.

Hence we have four «entities» in the FOURSEC that together make up the exposure (the complete circle), fig. 1:

- The lighting (representing the total of available light, natural and/or artificial)

- The aperture (representing the opening regulating the flow of available light into the camera)

- The exposure time (representing the time span for the recording of the light flowing into the camera)

- The ISO-setting (representing the sensor’s sensitivity to the light flow)

Mutually dependent settings

These entities depend on each other. If you change one entity, you have to adjust one or more of the other three to maintain the same amount of light for your exposure. Say a cloud comes in front of the sun and you get less available light (the lighting section of the circle becomes smaller), fig. 2:

To keep the circle full (the full sircle representing the ideal exposure), this reduction of the lighting section has to be compensated by increasing one or more of the other sections. In fig. 2 I have increased the ISO-setting (section) and kept the apeture and exposure time (sections) unchanged. So if the available light is decreasing, you can for instance increase the ISO-setting (set a higher ISO value to make the sensor more sensitive to light) to obtain the same exposure result.

Say you now also want to make sure that you avoid unsharp images due to camera shake, so you opt for a shorter exposure time (faster shutter speed). The available light is still the same, and you stick to the same ISO-setting. If you then reduce the exposure time (section) the only option you’ve got is to increase the aperture (section) and thus increase the flow of light into the camera, fig. 3:

Again the FOURSEC explains the situation perfectly (fig. 3): To maintain the amount of light ideal for the exposure we have to increase the aperture (the opening, the flow of light) as the light will be flowing onto the sensor for a shorter period of time.

Please note that I by the term aperture refer to the physical size of the aperture, not the f/number as the latter would not work in this model as a larger f/number means less light through the lens!

Explaining how a photograph was taken

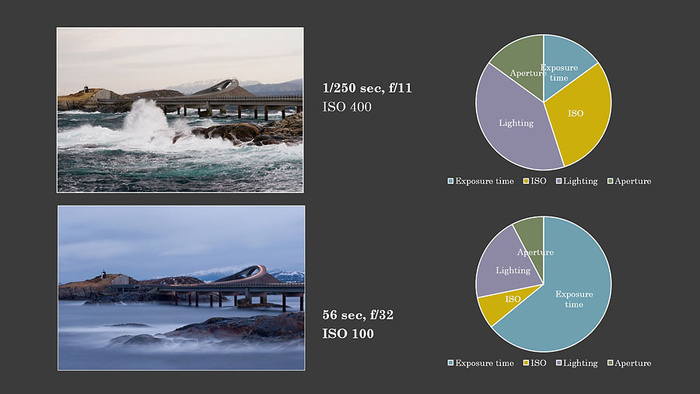

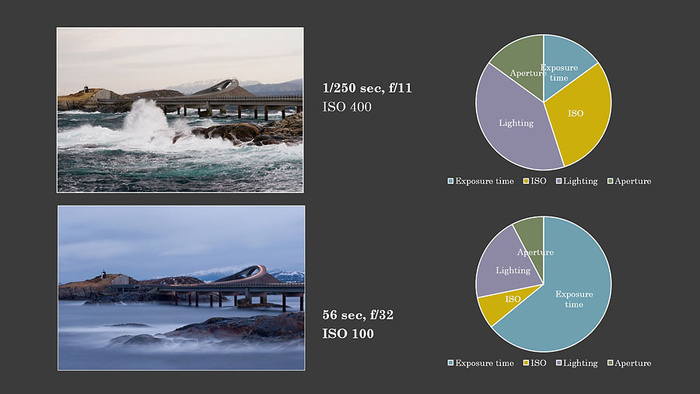

In addition to being a tool for understanding exposure as such, the FOURSEC can be used for visualizing the settings for a photograph when explaining how the picture was taken. See fig. 4 with pictures from the Atlantic Road in Norway:

Fig. 4

The upper picture was taken on an overcast day around noon. To stop the motion of the waves I opted for a relatively short exposure time (1/250 sec.). I also wanted a great depth of field (DOF) and consequently chose aperture f/11(greater f-number gives greater depth of field, but a smaller physical aperture). Giving priority to a short exposure time, and a relatively small aperture, I had to increase the ISO to obtain the ideal exposure. (As the sun alone provided the available light for the landscape, I could not increase the lighting.)

The lower picture was also taken on an overcast day but this time in the afternoon. This means that the lighting was on the decrease, hence the smaller lighting section in the lower circle compared to the upper circle. In this picture I wanted to have light trails from the cars for the whole visible distance of the road. As the cars were in the frame for ca. 55 seconds, I had to use an exposure time a bit longer than this and opted for 56 seconds (with the camera on a tripod). This is a very long time for letting light into the camera, so to get the ideal exposure I had to narrow down the aperture as much as possible to strain the flow of light (f/32), and in addition I had to make the sensor very little sensitive to light (reduce the ISO setting considerably).

Use of filters included

What then if the lighting had been stronger (if the lighting section of the circle had been larger)? Say I was already using the smallest possible aperture on my lens, and the lowest possible ISO setting on my camera, so these section of the circle could not be made smaller. If there was more available light (a larger lighting section) I would then have to reduce the exposure time (section) and I would not have managed to capture light trails all the way in the photo. I could of course have waited until dusk, but there would actually have been an other way around the problem. Now the introduction of the lighting section becomes even more useful. If there is too much available light, you can simply apply a tool for reducing the available light. By fitting a neutral density filter (ND filter) to the front of the lens you can stop some of the light from entering the camera. And voilà, the lighting section is reduced, allowing you to increase the exposure time (section) enough to get those light trails all the way! You are suddenly able to control every single section of the circle, and the FOURSEC model explains it all.

Win some, lose some

Exposure is all about balancing or giving priority to settings, about winning some and losing some. What you win or lose are for instance: You win a larger depth of field (DOF) by decreasing the aperture (larger f/number), but you lose light and must compensate by using a longer exposure time and/or a lager ISO setting. The larger ISO setting you use in this situation the shorter exposure time you win. So by increasing the ISO you may regain the exposure time you had before decreasing the aperture, say if you want to both freeze action/movement and win a large DOF at the same time. By using a larger ISO setting, however, you lose technical image quality, so this setting should be balanced to what other kinds of quality you want to win or lose in your picture, i.e. DOF or sharpness of moving objects. (When increasing the ISO setting the camera turns up the light volume electronically, and noise from the system will show in the image (grain and colour specks). You will also have photos with less detail in them as they actually will be underexposed at the outset.)

It is important to note that the sections in the FOURSEC model cannot be compared to each other mathematically. The model does not work like a traditional statistics pie with sections derived from calculations based on one specific entity. Exposure times are measured in seconds. Apertures as such are measured in millimetres, and the value representing the camera’s sensitivity to light is, well ISO. Thus the FOURSEC is to be applied and read only as a symbolic reference to the lighting conditions and the camera settings.